When the steel rod pierced his skull with lightning speed, throwing bloody pieces of brain tens of meters away, it seemed that young Phineas Gage would pass with the wind as a victim of an unfortunate accident. However, he miraculously survived, and the mention of his name raises hairs on the head to this day. It’s hard to say whether it’s more interesting that he survived at all, or how the loss of part of his brain affected his personality.

ACCIDENT

On September 13, 1848, near Cavendish, Vermont (USA), 25-year-old Phineas P. Gage was working as a foreman, preparing the ground for a railroad track for the “Rutland & Burlington Railroad”. His crew’s job was to pave a path through rock using explosives. Phineas Gage had done this hundred of times before. This time he instructed his assistant to cover the powder in the blast hole with sand, focusing his attention on talking to the other workers. Then, mistakenly convinced that what needed to be done was done, he began ramming the powder. The friction of the iron rammer against the rocks must have caused a spark because an explosion unexpectedly occurred.

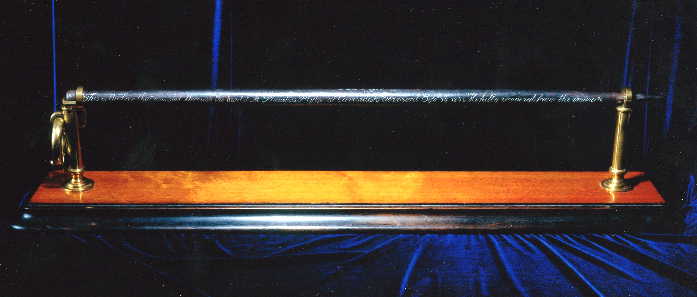

It was then that the 110 cm long pointed iron ramming rod, 3.2 cm in diameter at its widest point and weighing less than 6 kg, went through Gage’s head like a bullet, massacring his brain. It went through his left cheek just above the zygomatic arch, behind his left eyeball, piercing the cranial vault under the left basal forebrain, continuing through the brain, and then exited the upper and anterior part of the skull near the sagittal suture and bloodied along with parts of the brain about 20 meters away. Gage collapsed on his back, suffering convulsions of his limbs.

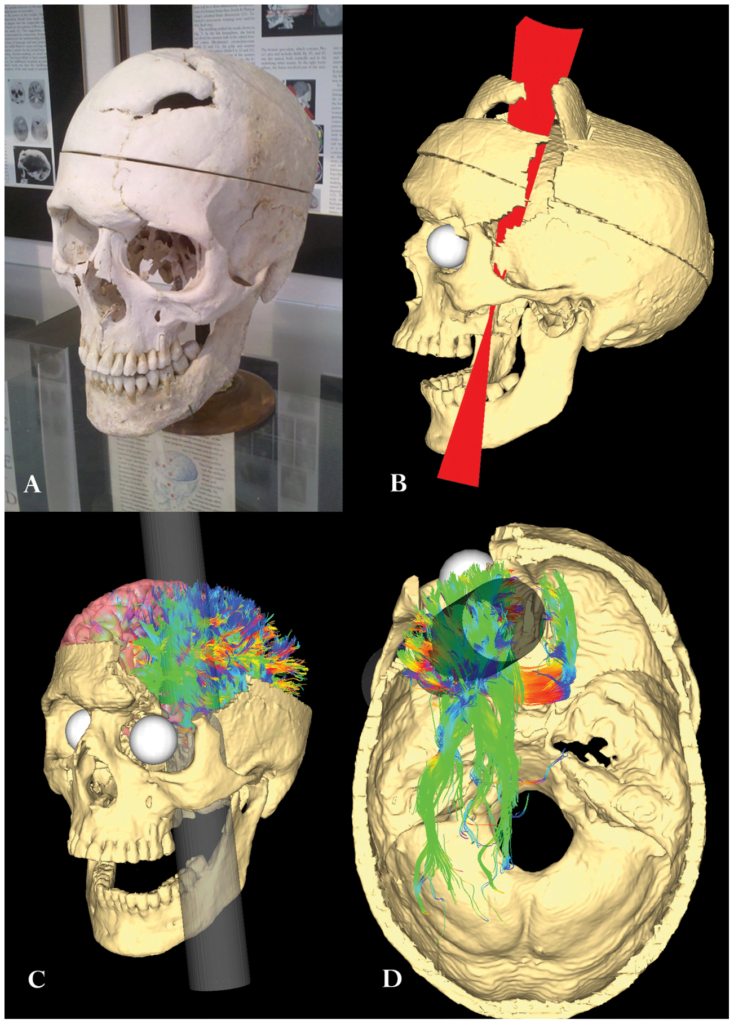

B-D) Projections of the results of three-dimensional modeling of the path of the iron rod through Gage’s skull and its effect on the structure of the white matter.

(source: Van Horn JD, Irimia A, Torgerson CM, Chambers MC, Kikinis R, Toga AW (2012) “Mapping Connectivity Damage in the Case of Phineas Gage”, PLoS ONE 7(5): e37454, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0037454.g001)

TREATMENT

The unfortunate man (it depends on how you look at it) not only survived the gruesome accident, but regained consciousness got up on his own two feet, and walked a few yards. His associates took him (and the collected skull fragments) to a young city doctor, Dr. John Martyn Harlow. This one removed small fragments of bone from the brain. He placed it in its place, as it protruded significantly from the skull, drained the blood, and placed the larger skull fragments in their place. He left only an opening for drainage. Gage himself was confident that he would be back to work in a few days. He said that was why he did not want to see his friends. Gage remained conscious most of the time. He recognized family, remembered the names of co-workers. His condition was variable. At times, he was delirious. After 10 days he finally lost vision in his left eye. He remained in semi-sleep for several days. The infection had set into the wound. The injured Gage was once again very lucky after the accident because Dr. Harlow was one of those doctors who were able to remove the abscessed tumor caused by the bacterial infection. Since then, the patient’s condition had steadily improved, so much so that on the 56th day after the injury, Dr. Harlow learned that his patient had been on the street in his absence. He forbade him to do so, but to no avail. Gage allowed himself daily outings, such as to the store. Finally, on November 25, about 2.5 months after the accident, he returned home. The wound had healed, covering his brain.

(public domain, source: Biographical history of Massachusetts: biographies and autobiographies of the leading men in the state, Volume 1, 1911)

CHANGE OF PERSONALITY

Dr. Harlow’s report indicated that Gage was considered the most efficient and capable foreman before the accident. The doctor wrote:

“He is fitful, irreverent, indulging at times in the grossest profanity (which was not previously his custom), manifesting but little deference for his fellows, impatient of restraint or advice when it conflicts with his desires, at times pertinaciously obstinate, yet capricious and vacillating, devising many plans of future operations, which are no sooner arranged than they are abandoned in turn for others appearing more feasible. A child in his intellectual capacity and manifestations, he has the animal passions of a strong man. Previous to his injury, although untrained in the schools, he possessed a well-balanced mind, and was looked upon by those who knew him as a shrewd, smart business man, very energetic and persistent in executing all his plans of operation. In this regard his mind was radically changed, so decidedly that his friends and acquaintances said he was “no longer Gage“.“

– dr Harlow

Researchers estimated that Gage lost about 11 percent of his white matter and about 4 percent of his frontal cortex in the accident. The extent of the damage was debated, but it appears to have affected both the left and right prefrontal lobes. This part of the brain, according to neuroscientists, is responsible for rational decision-making and emotional control, among other things. In people with psychopathic tendencies, less activity in this area can be observed. Symptoms may include uncritical thinking, antisocial behavior, or a tendency to take greater risks. Sometimes a person has difficulty controlling emotions, especially in stressful situations. A similar mechanism can be observed when the amygdala becomes more active. Simplifying these two anatomical structures: the prefrontal cortex (the rational part) competes with the amygdala (the impulsive part). The mental abbreviation is quite large, but it is more or less like this.

There was also damage to many neuronal pathways between anatomical structures of the brain: for example, between the hippocampus, amygdala and insula, and frontal areas. We know that the brain is neuroplastic, so in Gage’s case, there was undoubtedly a reorganization of neuronal connections. This happens with most injuries. For example, after a loss of vision, the part of the brain responsible for seeing can somehow be taken over by the other senses. Hence, there is a sharpening of the other senses.

See also how brain neuroplasticity works during sleep in this article: DREAMING PROTECTS THE EYESIGHT FROM THE ATTACK OF OTHER SENSES

Science confirms the possibility of such personality change as Harlow described. Traumatic damage to the frontal cortex can cause profound behavioral changes, mood changes, deficits in planning, social functioning. Similar effects can also cause neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s because it affects brain networks involving frontal lobe connectivity.

FURTHER FATE OF GAGE

The unfortunate man was unable to return to his previously held position. This alone may have been the source of his considerable dissatisfaction. It is said that he traveled throughout New England and Europe, earning money by showing the effects of his injury and the iron rod. What is certain is the fact that from 1851 he worked in a stable and later as a stagecoach driver. First for 18 months in the state of New Hampshire and then for 7 years in Chile. In 1859, after his health deteriorated, he went to live with his mother. A year later, barely 36 years old, he died of complications from epileptic seizures. It was the accident of years earlier that was thought to have contributed to his epileptic seizures. No autopsy was performed. Dr. Harlow himself did not learn of his patient’s ailments and death until several years later. With the permission of his family, Gage’s body was exhumed. His skull and the iron rod are still housed in the Warren Anatomical Museum at Harvard Medical School.

(source: Warren Anatomical Museum, Harvard Medical School, https://collections.countway.harvard.edu/onview/items/show/26376)

CONTROVERSY

Some of the coverage of Gage was greatly exaggerated, especially in terms of the changes in his personality that were sometimes exaggerated. It was folklore to consider him a circus attraction. This was more due to the association of lunatics with these venues. His photographs after the accident do not depict him as such. However, the changes in Gage’s personality and cognitive function were not necessarily so significant over a long period of time. In fact, little is known about Gage’s personality before the accident. Therefore, his case was quite susceptible to the addition of whatever happened to fit under a particular scientific (or now pseudo-scientific) theory. Note that for many years Gage held positions of responsibility and was tied to one place. This tends to indicate a settled life situation. Dr. Harlow and Professor of Surgery Henry J. Bigelow of Harvard University could say the most about Gage. The latter also examined the unfortunate man while he was still alive, too. Bigelow even portrayed Gage as an alcoholic, which, however, is not confirmed by Harlow’s earlier accounts. The latter, on the other hand, reported that the iron rod accompanied Gage for the rest of his life, which cannot be entirely true since the rod was at Harvard until 1854. The conflicting accounts of Gage’s personality are most likely rooted in the scholarly conflict over phrenology. It is now considered a pseudoscience. It assumed that mental abilities and traits depended on the shape of the skull. Each part of the cerebral cortex was supposed to be responsible for different mental functions. Harlow was a supporter of this theory while Bigelow believed otherwise. However, the most heated discussion took place only after Gage’s death. So he could not say too much about his subject.

(source: Jack and Beverly Wilgus collection, now at the Warren Anatomical Museum, Harvard Medical School)

SIGNIFICANCE

Gage’s case continues to be debated among neuroscientists. It has been no less significant in studies of human brain function and the effects of brain damage on behavior and functioning. For ethical reasons, it is not possible to conduct a study of an analogous case because the probability of a similar event (surviving an injury like Gage’s) is low, and no one would drill a hole in someone’s head to find out. What’s possible is to transcranially electrically stimulate specific areas of the brain and see how that affects specific functions. Note, however, that we are talking about the second half of the 19th century when the brain was even more mysterious than it is today and neuroscience was still in its infancy. Research methods were not as advanced as they are today. Dr. Harlow and Professor Bigelow could only dream of functional magnetic resonance imaging. And as strange as it sounds, although they didn’t have the current technological advances, they did have the real-life case of Gage, which set the stage for neuroscience.

Sources:

- J. M. Harlow, (1848). “Passage of an iron rod through the head”. Boston Medical and Surgical Journal. 39 (20): 389–393, https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm184812130392001,

- J.M. Harlow (1868). “Recovery from the Passage of an Iron Bar through the Head” Publications of the Massachusetts Medical Society. 2 (3): 327–47. Reprinted: David Clapp & Son (1869), https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Recovery_from_the_passage_of_an_iron_bar_through_the_head,

- H. Damasio, T. Grabowski, R. Frank, A.M. Galaburda, A.R. Damasio, “The return of Phineas Gage: clues about the brain from the skull of a famous patient”, Science 20 May 1994, Vol. 264, Issue 5162, pp. 1102-1105, https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.8178168,

- Van Horn JD, Irimia A, Torgerson CM, Chambers MC, Kikinis R, Toga AW (2012) “Mapping Connectivity Damage in the Case of Phineas Gage”, PLoS ONE 7(5): e37454, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0037454.