The more money in a lost wallet, the greater the chance of recovering it. That’s the surprising conclusion researchers came to after a study conducted in 355 cities from 40 countries. Can this research say something about honesty in a given country? Are Poles more honest than Americans, the British, and the Chinese least than everyone else?

COSTLY EXPERIMENT

The experimenters used 17,333 “portfolios” (and let someone tell you that scientific research doesn’t require funding – in total, the study cost about $600,000 USD). In private and public institutions, such as hotels, cinemas and police stations, they informed that they had found the wallet, but they did not have time to look for its owner. They asked for the case to be taken care of and left. The “wallet” contained a business card with contact information. With them was only an email address. Also thrown in was a key, a shopping list, and, depending on the attempt, a small amount of money – exactly the equivalent of 13.45 US dollars.

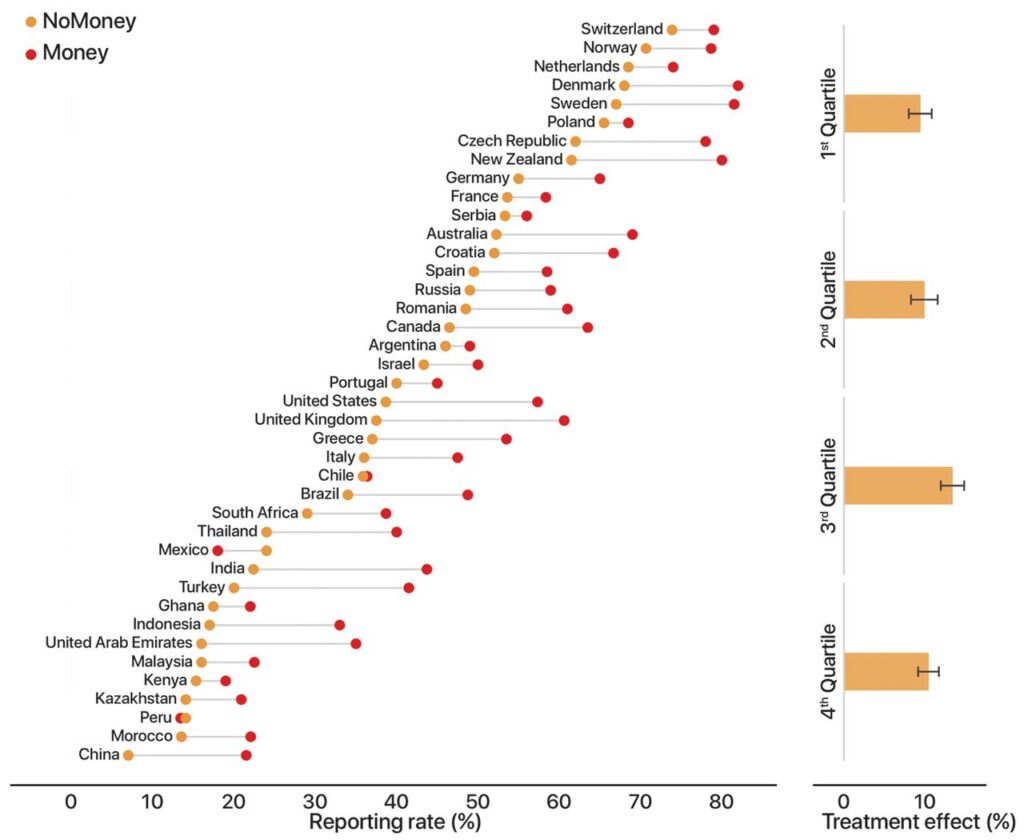

(Left) Share of wallets reported in NoMoney (US$0) and Money (US$13.45) conditions, by country. The amount of money in the wallet is adjusted according to each country’s purchasing power.

(Right) Average difference between Money and NoMoney conditions across quartiles based on absolute reporting rates in the NoMoney condition. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean.

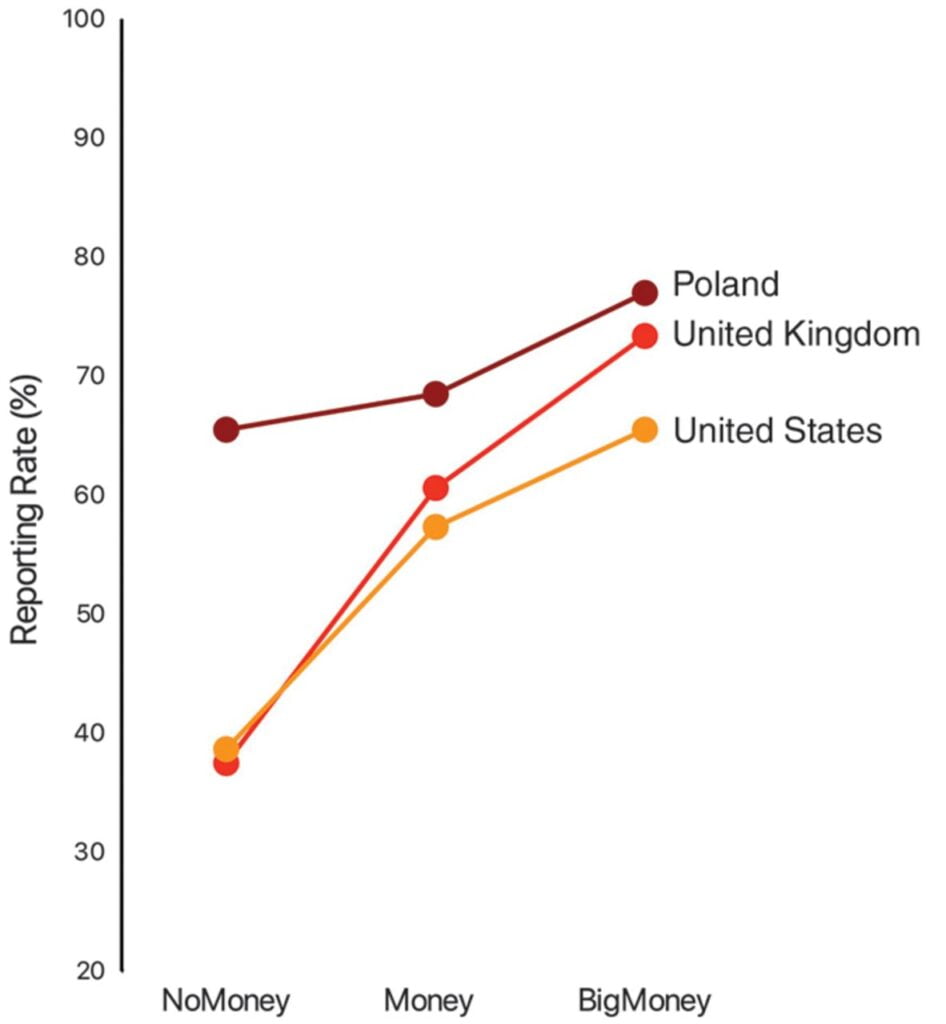

It turned out that when there was money in the “wallets” they were more likely to be returned. Therefore researchers extended the experiment to three countries (USA, UK, and Poland). They added to the wallets a larger amount of money, to the equivalent of 94.15 USD

Share of wallets reported in the NoMoney (US$0), Money (US$13.45), and BigMoney (US$94.15) conditions.

The results were also counterintuitive, as more money translated into more returns – just like in the graph.

CONCLUSIONS

There was thus a suggestion that, for those finding the wallet, the losses resulting from reevaluating their person by considering themselves a thief were more valuable than the economic loss of the money found. The misappropriation of small amounts was not supposed to cause as much discomfort as the misappropriation of large amounts. Paradoxically, the idea emerges that it is better to lose more money because then the chance of getting it back is greater. It is interesting not only that people were more likely to return wallets containing larger amounts of money, but that in each of the countries surveyed the “wallet” was returned less often if there was no money in it at all. Surveys conducted later seemed to confirm the above. Perhaps the finder considered it a small loss to the owner…

The research also suggests how levels of honesty vary by country. One might be tempted to suggest that people in Switzerland, the Netherlands, Sweden, Norway, and Denmark where 70-85% of “wallets” were returned are more honest than people in China, Kenya, and Mexico where the return rate was less than 30%. However, there is a rather large “BUT”….

I WAS WRONG TOO

When I reported about the study on Instagram shortly after it was published, I didn’t know how misleading the title of the study and its findings were in terms of assessing the level of honesty in a country. Let’s start with the title: “Civic honesty around the globe“. It undoubtedly indicates that the subject of the study is what the title indicates, because how could it be otherwise. To paraphrase: we examined the level of honesty of people in different countries. The research article in question has resonated not only in the scientific community. Consequently, the researchers received a wave of criticism mainly from behind the Chinese wall. Thus, one by one.

CULTURAL AND SOCIAL CONTEXT

- The researchers failed to take into account, first of all, that hardly anyone uses e-mail in China. Chinese people mainly communicate by phone or using the WeChat platform. In response to the allegations, it was pointed out that most of the institutions where the “wallet” was left use email. However, this way of communication is mainly used in business relations and not very willingly. Besides, each company or public institution may have its own rules regarding the use of this communication channel. What’s more, some of the emails could be filtered by Chinese providers, even though the experimenters set up their own work server.

- In addition to the above, commenters on the study also pointed to the availability of lost items boxes. The researchers had no way of knowing how many of the “wallets” were dumped there. They also confirmed that a similar arrangement is popular in Japan and they found lost and found items on the official lost and found pages. Except that they had no way to recover them because they could not confirm the identities of the fictitious people on the business cards. For this reason, they felt compelled to exclude Japan from the experiment, but no longer China.

- The “wallet” also contained a key, which should prompt active help to return the lost item. However, it has a different value depending on the country. In China, a key usually opens the door to an apartment. Whereas in European countries, it is more likely to apply to the office to the entire building.

- The most popular payment method in the middle country is mobile payments, which makes leaving cashless reliable.

- Of course, the differences do not apply only to China and the rest of the world. But they are a good example, showing the study’s methodological flaws, or at least in the context of the stubbornly popular title.

- There was no way to determine whether the front desk worker to whom the “wallet” was given was, for example, a seasonal worker from another country.

- Different countries have different legal incentives for honest behavior. They also have different explicitly stated obligations in this respect. In Poland, for example, this is regulated by the Lost Property Act. It says to whom the item should be returned, depending on the item. With the right conditions, there is also a reward of 1/10th of the value of the item.

See also: HE FOUND $ 17 THOUSAND AND HE GAVE IT TO FOOD BANK

CASE IS NOT A WALLET

Regardless of the country, it’s rather arguable that the document case used is not very much like a wallet and that’s why I put it in quotes. A more realistic social experiment, albeit on a smaller sample, was conducted in China, where real wallets were used with the possibility of wider communication: by phone, via WeChat, and email (link in sources). The return rate than did not differ from that in the countries at the top of the study in question.

NIGERIAN SCAM AND OTHER SCAMS

One commenter rightly pointed out that the designed experiment may have seemed like a street scam. Indeed, there are different variations of the dropped wallet scam (forthcoming article on social engineering scams – worth subscribing to).

“The best counter approach of the “dropped wallet” scam, which is the country first part of the lecture of almost all the parent to their children when they take their first trip alone, is that “you toss that away and stay out of it, no matter how much money you see in that” This family tip in Chinese culture is just the equivalent of “Do not take drinks from strangers” in the US or Europe.”

– Gideon S (commentator of the research)

The gendarmerie in Kenya took a similar view and arrested the research assistant for suspicious activities. Therefore, data collection in Malindi city was not completed. Furthermore, the research assistants were recruited exclusively from two German-speaking universities. Thus, they may have been less reliable than native-speaking locals – the researchers spoke English.

WE RESEARCH HONESTY, BUT WE DID NOT RESEARCH IT

Sounds absurd, to say the least, but that’s how I understand it. To accusations of a misleading title, the researchers responded:

“We chose our title because our paper documents a global phenomenon — in virtually all countries, wallets that contained money were more likely to be reported. Our results suggest this occurs because people around the globe care about viewing themselves as an honest person. With the benefit of hindsight, however, we can see how our title could give the wrong impression about cross-country differences. That said, reading the paper abstract alone would be enough to rectify this misunderstanding.“

Personally, I’m not convinced by this. Did the authors of the study just admit to a clickbait title? And in the context of research about fairness, is it fair? In my opinion, the fix should come from the authors themselves. In other words, the level of civic honesty was studied – after all, that’s what the study was titled – but there was no desire to show that one country’s society is less honest than another. I agree with the opinion that in such a situation it would have been appropriate to change the title for example to: “The effect of financial incentive on honesty.” Especially since the researchers themselves admitted that the title is misleading. It should then be made clear that the research did not take into account the cultural and social context. There are many other studies where attempts have been made to examine honesty. For example, it has been tested whether subjects would cheat during a game if doing so would give them an advantage and thus a real material benefit.

“The word choice in the title and main text of the study is totally misleading to encourage misunderstanding of ‘reporting rates’ as ‘honesty rates’, which clearly is not equivalent. Such biased word choice in the paper leads me to speculate that the authors were doing it purposely.

Overall, despite the interesting results on psychological response to financial temptation, the study comes with a huge flaw in the experimental design and misleading word choice in the title and main text. We must ensure that academic research across cultural regions considers social habits so that to avoid claiming fallaciously or stimulating prejudice among the general public.“

– Bo Xia, Graduate student, NYU Langone Health (commentator of the research)

AND WHAT IS HONESTY ANYWAY?

The experimenters’ assumption also remains key. Commenting on the paper, Professors Xinyue Zhou of Zhejiang University and Yacheng Sun of Tsinghua University pointed out the possibility of alternative ways of morally appropriate behavior, other than sending an email:

“Importantly, these alternatives are also morally correct; whether actively contacting or passively waiting for the owner is therefore non-diagnostic about whether the receiver is honest. The specific behavior that a receiver tends to adopt depends on his/her economic and psychological costs and the culture-specific norm. Cohn et al.’s measure for honesty assumes that the only morally correct way to handle a turned-in wallet is to contact the owner. We disagree. Active helping and honesty are distinct concepts. The notion that email contact rate faithfully reflects the level of civic honesty is potentially misleading.”

The acceptors of the “wallet,” who by the way had no way of refusing to accept it, could have simply waited until the owner was looking for his loss. Or they could have decided that since he didn’t, it wasn’t very important to him. Think for yourself what you would do if you lost your wallet. Personally, I would walk the last route where it potentially fell off for me. I would look at places where I used it and ask if anyone had found it. I could look through local groups on a social networking platform popular in my country and hope that an announcement was posted that my loss was found. As you can see, depending on the country, the obligations of a certain behavior did not have to focus on electronic communication.

IMPORTANT TITLE

Despite all this, the article, or rather its title, in the prestigious scientific journal Science is doing well. It is not likely to change.

The article was one of the most cited in 2019. By the time its reviews appeared, a slew of articles had been written, and the issues raised were unlikely to be revisited. Research reviews are worth waiting for, and going through the – apparently – rigorous requirements of a journal like Science does not exempt one from critical thinking.

The only conclusion that can be drawn is that the more money in one’s wallet, the greater the chance of getting it back. However, it is hard to say whether there is a limit to where people will be more likely to be dishonest. Are the Chinese less honest than Poles, Brits, and Americans? First, even if they are, this research in no way supports that. Secondly, let’s not generalize any society, because we will build stereotypes and radicalize views based on prejudice. The consequences of the idea formed on this ground may be lamentable.

So that I don’t just complain, I appreciate the effort that went into the very expensive and extensive research. Taking into account cultural and social differences, as well as different possibilities of honest behavior than in the assumed experiment, one has to conclude that people are generally more honest than it intuitively seems to those surveyed, including economists. It is only unfortunate that, despite many objections to the suggested title of the research, the researchers wandered into contradictions. On the one hand, they claimed that the differences between countries were not the most significant. On the other hand, they explained that the results were basically in line with data on public corruption, tax evasion, or diplomats (covered by diplomatic immunity) violating parking bans.

The title of the study itself is quite bold for the researchers’ statement that “Cross-country comparisons were discussed only in 2-3 sentences at the end of the paper, primarily to highlight its potential use as a data set for future scholarly research. In the paper we did not single-out or discuss reporting rates for any particular country, because that was not the point of our paper.” If that wasn’t the point, then what is the problem?

Sources:

- Alain Cohn, Michel André Maréchal, David Tannenbaum and Christian Lukas Zünd, Civic honesty around the globe, Science 365 (6448), 70-73, doi.org/10.1126/science.aau8712;

- Polish Act of February 20, 2015 on found property (Journal of Laws of 2015, item 397, as amended), isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20150000397;

- 歪果仁研究协会 Ychina, Putting the Public’s Honesty to the Test in China…, www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lg6WG6pRcFM.